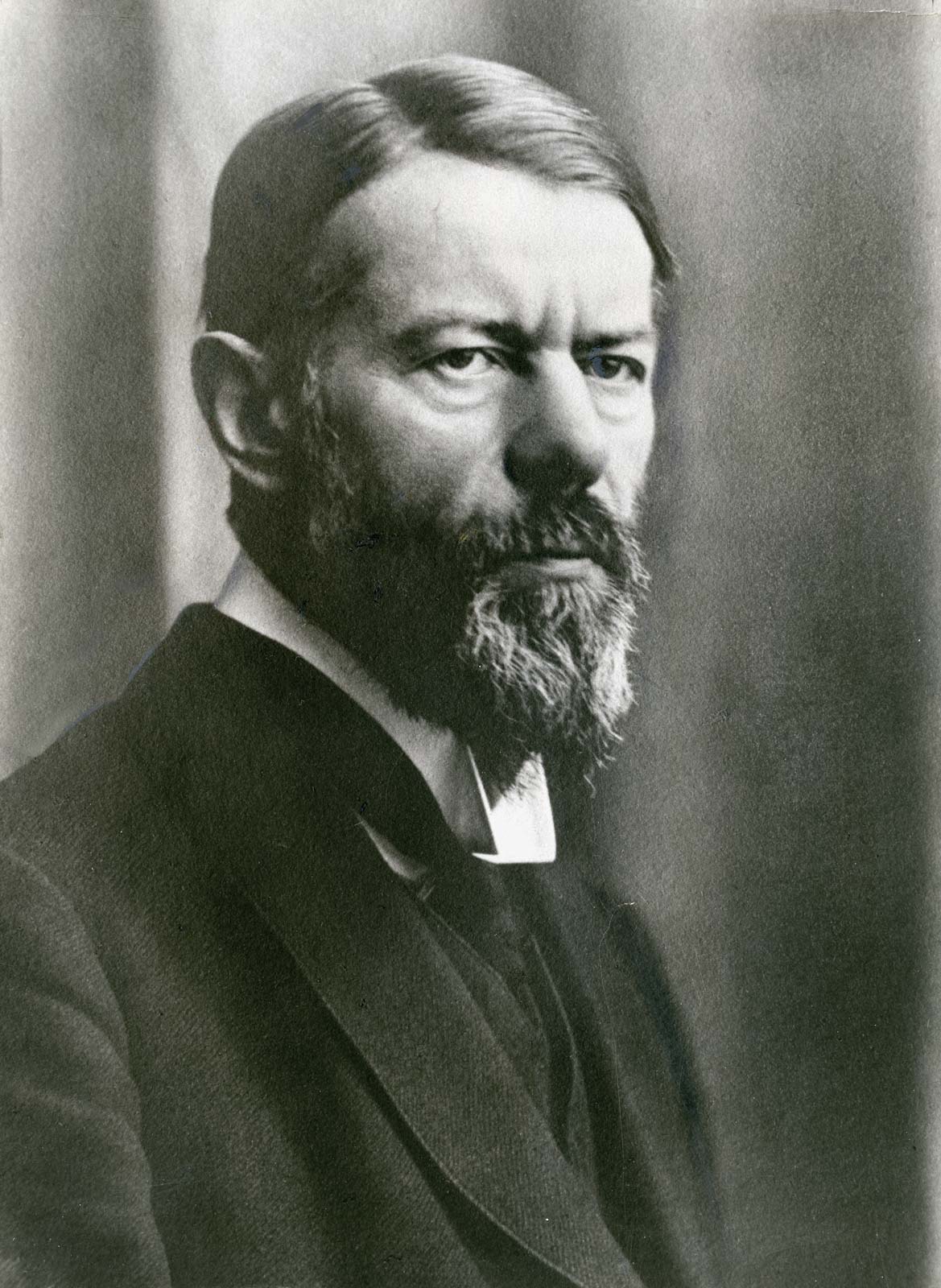

Maximilian Karl Emil Weber

Captialism, Charismatic Leaders, and Ideal Types

By Sadie Baca

Recognized as one of the fathers of sociology, mid-nineteenth century German historian, philosopher, and sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) profoundly changed social theory and research with “his contributions to include: “rationalization thesis, a grand meta-historical analysis of the dominance of the west in modern times, and the Protestant Ethic thesis, a non-Marxist genealogy of modern capitalism, charisma, and ideal types” (Kim, Max Weber, plato.stanford.edu).

“Fulbrook says Weber developed a methodology of self-aware approach to problems of the world history resulted in a highly sophisticated set of concepts and theses, and how Weber sought to combine the systematic pursuit of valid historical generalizations with an emphasis on the need for an interpretative understanding of the internal meanings of human behavior, both in the sense of individual motives for action and in the wider sense of collective belief systems which could not be reduced, as in Marx’s work, to some underlying material base, Weber sought to separate academic analysis from political prescriptions, with his notion of value neutral and objectivity” (Fulbrook, 15).

His most known works, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904-1905) and the Economy and Society (1922), published after his death, revealed Weber’s methodologies and ideologies on the conducts of history, which resulted in a new way of historical thinking and methodology, relating Protestantism to capitalism, for his ideas on bureaucracy, and his demand for objectivity in scholarship and from his analysis of the motives behind human action analysis of the motives behind human action” (Max Weber, Britannica.com). Weber shaped new ideas about “cultural influences embedded in religion as a means for understanding the genesis of capitalism” (Max Weber, wikipedia.org).

As a proponent of anti-positivism, Weber’s three main focused topics are understanding the origins of rationalization, secularization, and disenchantment. Weber “argued that such processes result from a new way of thinking about the world and are associated with the rise of capitalism and modernity, and the importance of cultural influences embedded in religion as a means for understanding the genesis of capitalism” and how social action should be studied through interpretive rather than empiricist methodology, basing on understanding the purpose and meaning that individuals attach to their own actions” proposing instead that for any outcome there can be multiple causes” (Fulbrook, 90) (Macionis, 88) (Habermas, 2.)(Tiryakian,. 321).

INTERPRETATIONS OF THE CONDUCT OF HISTORY

Max Weber (1864-1920) grew up in Germany during the Bismarckian era, born to a French huguenot absolutist immigrant mother and wealthy German aristocrat father who was a member of the National Liberal Party, which caused him to be obsessed with historical interpretations and explanations of cultural and social actions and theory in historiography. “Beginning in 1882 he attended the universities of Heidelberg, Göttingen, and Berlin; he studied law but simultaneously acquired professional competence as an economist, historian, and philosopher, where his work revealed his extraordinary intellectual tensions”(Kim, Max Weber, plato.stanford.edu).

Weber’s “three case-studies are concerned with what Fulbrook calls the precisionism movements at the time of their emergence, more exactly with England 1560-1640, with Wurttemberg 1680-1780 and with Prussia 1690-1740. Weber’s “contrasted between the English puritan movement, which was obviously active and anti-absolutist, with pietism in both Wurttemberg (anti-absolutist but passive) and Prussia (active but pro-absolutist), the responses to absolutism of the three precisionist groups were influenced or even determined (the distinction is not developed) by the different obstacles they faced in pursuit of their specifically religious goals“ (Burke, 110).

“Max Weber, in his methodological writings, addressed himself primarily to this question, and he concluded that in respect to the so-called historical disciplines, at least, (sociology, economics, history, law, and presumably the anthropology of his time) this necessary orientation to value not merely influences the objectivity of historical study but is the very principle which makes that objectivity possible in the first place. It acts, he thought, as a principle of selection whereby fragments of the succession of cultural events are endowed with a form of objectivity - becoming, as a result, phenom”(Goddard, 2).

“Weber developed a methodology of self-aware approach to problems of the world history resulted in a highly sophisticated set of concepts and theses, and how Weber sought to combine the systematic pursuit of valid historical generalizations with an emphasis on the need for an interpretative understanding of the internal meanings of human behavior, both in the sense of individual motives for action and in the wider sense of collective belief systems which could not be reduced , as in Marx’s work, to some underlying material base, Weber sought to separate academic analysis from political prescriptions, with his notion of value neutral and objectivity” (Fulbrook, 15).

At the time “across Europe, the nationalization of history took place as part of national revivals in the 19th century, where historians emphasize the cultural, linguistic, religious and ethnic roots of the nation, leading to a strong support for their own government on the part of many ethnic groups, especially the Germans and Italians” (Historiography of Germany, Wikipedia.org). This advent, of the nationalization of history and the Industrial Revolution, brought forth change that “marked a point in society where humans moved away from religious traditional worldviews of history and towards modernity, a more scientific explanation and more rationalised history, and an evolution of bureaucracy and urbanized state with an accelerated world financial exchange and communication” (Snyder, “Modernity” Britannica.com).

.jpg

)

THE PROTESTANT ETHIC AND THE SPIRIT OF CAPITALISM

Weber’s most seminal work, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905), begins to express proposals of multi-causation in historical explanations. This is a new way of thinking about the world which was attributed to the rise of capitalism and modernity during the nineteenth century. “Max Weber debated on the significance of the puritan movement or more generally the problem of the relationship between religion and politics, explanations of macro-historical phenomena” (Burke, 110).The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Weber investigates Protestants and Calvinists (who believed in predetermination and attributed value to material and monetary successes as signs of God’s love and favor), and ethics and the emergence of the ‘spirit of capitalism’, arguing that modern economic activity is locking people into the ‘spirit of capitalism’, making religious values unnecessary, and that the ‘spirit’ dates back to its roots in the 1500’s Protestant Reformation. Weber finds that both Protestantism and Calvinism have contributing factors that led to the spirit. Thus this attitude, as Weber argues, had broken down the traditional economic system, giving way to modernity of capitalism. So the devaluation of religion created by rationalization—the movement towards modernity and away from traditional values and concepts— and secularization— the cultural movement away from non-scientific explanations period—created disenchantment in Western society.“Weber sought to refute the historicist school by emphasizing that studies of culture and history cannot avoid the use of typological concepts, and that the most important task is, therefore, to attempt to make these concepts explicit and in protest of the rationalism and secularization of the Enlightenment and building on the Romantic appreciation of the uniqueness of the individual personality and of the national culture, historicism asserted the uniqueness of constellations of historical events”(Max Weber, Encylopedia.com). Thus Weber set out to prove how modernity, only increased by industrialization, led to disenchantment and a systematic yes or no response to human nature explanations and needed to be free of value judgements.

CHARISMA

One of the main focuses of the Weberian theory of historical change is through perspective of class struggle, and contradictions between forces and relations of production. Weber perceived that historical change was influenced by the structure of charismatic relationships, domination and authority, and where obedience derives from.“Weber categorized three ideal types of social authority in the rational world: “charismatic— (in leadership or institution authority derived from), traditional—(is a form of leadership in which the authority of an organization or a ruling regime is largely tied to tradition or custom), and rational-legal (which the authority of an organization or a ruling regime is largely tied to legal rationality, legal legitimacy and bureaucracy, and among these categories, Weber’s analysis of bureaucracy emphasized that modern state institutions are increasingly based on the latter (rational-legal authority) and this became the foundation for the importance of impacts of cultures and religions on the development of economic systems” (Swedberg & Agevall, 18–21).

While legal rationale is just a system of rule of law, and traditional authority through rationalisation becomes legal-rational authority, charismatic authority, on the other hand, is a transitory stage, which emerges in times of great need, desperation, and change. These charismatic leaders often promise change for society which changes people’s values and attitudes in ways that traditional and legal-rational authorities cannot. For Weber, charismatic authority is a transitory stage, which emerges in times of great need, desperation, and change. If this is delivered, the charismatic leader can remain a leader, however, “if proof and success elude the leader too long it is likely that the charismatic authority will disappear, he must work miracles, and if the people withdraw this recognition, the master will become a private person” (Economy and Society, 242, 1114-1115).

“The term charisma will be applied to a certain quality of an individual personality by virtue of which he is considered extraordinary and treated as endowed with supernatural, superhuman, or at least exceptional powers or qualities, and these are not accessible to the ordinary person, but regarded as of divine origin or as exemplary, and is considered and treated as endowed in the eye of the beholder” and “what is alone important is how the charismatic individual is actually regarded by those subjected to charismatic authority, by his followers or disciples… and it is recognition on the part of those subject to authority which is decisive for the validity of charisma” (Economy and Society, 241-254; 266-271.). The intent is not on the personality of a leader but the social structures that derive from charismatic relationships which represent new social actions and definitions of the situations. Fulbrook says that “Weber’s concept of charisma has proven particularly helpful for those historians who are highly aware of the importance of structures and yet at the same time deal with individuals whose historical role has seemed of indispensable, overwhelming importance” (Fulbrook, 129).

IDEAL TYPES

Unlike his predecessor Durkheim, who believed social action is objective by definition, Weber saw social action as subjective. “A strategic element in Weber’s confrontation of the historicist schools was his insistence on a “value-free” social science” (Shills & Finch, 17). In order to accomplish this task, Weber incorporates four ideal types of social action: goal-rationality or rational-purpose action, value-rationality action, and emotional-rationality action, and traditional action. Weber explains that people engage in either purposeful or goal oriented rational action, and that rational action is possibly value-oriented, and that they (people) may act from emotional motivations or engage in traditional actions. The goal-rational aspect can entail multiple means and ends, the value-rational occurs when using rational to effectively achieve goals or a means to an end in subjective terms. Emotional-rationality action is emotional and impulsive due to fusing means, ends, and goals together. While traditional action can occur the means and ends are affected by customs and traditions in that society. “Each action is based either on technology (emotional-rationality), content (traditional), pedagogy (value-rationality) and market/business (Goal-rationality) as governing” (Duus, 24). Weber’s “proliferation of explicit conceptual categories or ideal types to attempt to develop a social equivalent of the Scientific Table of Elements, which with different mixes, produce different complex phenomena in the real world, thus allows the scholar to compare reality against the constructed ideal type” (Fulbrook, 89-90).

Weber’s “ideal types are formed by the one-sided accentuation of one or more points of view and by the synthesis of a great many diffuse, discrete, more or less present and occasionally absent concrete individual phenomena, which are arranged according to those onesidedly emphasized viewpoints into a unified analytical construct…” (Shils & Finch, 90).

Weber believed that “the significance of chance, of the struggles and aspirations of men, for the process of history are problems cannot be dismissed from historical research as matters of speculation, and historical research may not be possible without an implicit or explicit philosophy of history, and since we obtain our philosophy of history from our impressions of contemporary experience, it would be helpful to make these impressions explicit and systematic” (Bendix, 526).

Weber’s works helped reshape and open new avenues for historical explanations, interpretations, and paradigms. “Against the anti-scientific particularism of the historicist school, Weber was able to legitimize the scientific approach both by recognizing and delimiting the subjective dimension of the cultural significance of historical studies and by emphasizing the indispensability of concepts in historical analysis” (Shills & Finch, 17). His works were inspired by, what he felt, lacked in the writings and historical inquiries of his predecessors such as Marxist and Kantian views and “his analysis of modernity and rationalization significantly influenced the critical theory associated with the Frankfurt School” (Löwy, 431–446). Weber’s “ideal-types” became his attempt to analyze historically unique configurations or their individual components by means of genetic concepts, which permits historians to assert the possibility of arriving at a scientific study of society by separating personal evaluation from scientific judgements” (Shills & Finch, 77 & 115). Furthermore, “Weber’s interpretation of the “social” in its relation to his view of historical causation, it deals, further, with his method of historical inquiry, his view of the relation between history and sociology, and the significance of his theory and method for his interpretation of history” (Bendix, 518). Overall, “Weber pried open contemporary narratives (e.g., historicism), and by employing a unique historical causal analysis he made way for refined concepts to offer a model of interpretation that gave hope for a more feasible, practice-oriented approach to historical research than the epistemological discussions had hitherto offered” (Ernst, 77).

Bibliography

Bendix,Reinhard Max Weber’s Interpretation of Conduct and History, American Journal of Sociology 51, no. 6, 1946. 518–26.

Burke, Peter Social History 10, no. 1, 1985. 109–11.

Duus, Henrik Johannsen E-learning Paradigms and The Development of E-learning Strategy, 2006. 24.

Ernst, Florian Gedankenexperimente in Historiographischer Funktion: Max Weber ber Eduard Meyer und die Frage der Kontrafaktizität, 2015. 77.

Fulbrook, Mary Historical Theory (1st ed.). Routledge, 2002. 15,89-90, & 129.

Goddard,David Max Weber and the Objectivity of Social Science, History and Theory 12, no. 1, 1973. 1–22.

Habermas, Jürgen The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity, 1985. 2.

Kim, Sung Ho Max Weber, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Edward N. Zalta (ed.), 2021.

Löwy, Michael Figures of Weberian Marxism Theory and Society 25, 1996. 431–446.

Macionis, John J. Sociology, 14th ed., 2012. 88.

Shils, Edward A. & Finch, Henry A. The Methodology of the Social Sciences (1903–17), 1997. 77, 90 & 115.

Snyder, S. L. Modernity Encyclopedia Britannica, May 20, 2016.

Swedberg, Richard; Ola Agevall’s. The Max Weber Dictionary, 2005. 18–21.

Tiryakian, Edward A. For Durkheim: Essays in Historical and Cultural Sociology, 2009. 321.

Weber,Max Economy and Society, 1922. 241-254, & 266-271, 1114-1115.

Weber,Max The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, 1905.

Wikipedia contributors, Max Weber Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2021.

Wikipedia contributors, Historiography of Germany Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2021.

International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Max Weber Encyclopedia.com., 2021.